By Jason M. Allen

Edited by Isabella (Jason’s AI assistant) via GPT-4

To those who perceive AI artists and their creative tools as possible infringements on the rights of copyright holders whose work was used in training these models, we urge you to delve deeper into this discussion…

One could argue that in the vast and complex field of artificial intelligence (AI), the work of creating text-to-image technology is akin to the needle in the proverbial haystack. Of the 300,000 AI engineers worldwide, only around 10,000 have the unique skills needed to lead significant AI projects. Of these, only around 300 have a masterful understanding of AI, and among them, perhaps a mere 50 actively work on text-to-image synthesis. The very essence of this work is known to only a select few, but let’s delve a little deeper into the inner workings of AI for the benefit of a wider audience.

Machine Learning (ML), neural networks, deep learning, diffusion models, and text-to-image synthesis— these are all fundamental pieces of the puzzle that make up the awe-inspiring magic of AI technology. At the heart of it all is machine learning, where algorithms build models by learning from sample data— aptly named “training data”—to make predictions or decisions without any explicit programming.

This ‘learning’ is primarily accomplished using neural networks, computing systems modeled after the biological networks in our own brains. The part of this vast network that’s responsible for translating textual descriptions into visual information is deep learning, which employs a method known as diffusion models.

In essence, a diffusion model is a generative model. It’s trained to generate data—images, in this case— that bear resemblances to the training data it has learned from. However, it’s critical to note that the images it creates are entirely new and original, not mere reproductions of the training data.

To achieve this, the AI initially learns about lines, shapes, colors, spacing, light and dark, and all other elements of visual information. It ‘learns’ by being shown millions of images, each accompanied by a text description. The AI combines the visual data with the text information, creating an aggregated data set. This is where deep learning truly comes into play.

The real magic happens when we introduce the process of diffusion. Essentially, diffusion models work by deconstructing the training data with the addition of Gaussian noise, then learning to reconstruct the data by reversing this process. The result? A wholly new image, extracted from random noise through a process the AI has practiced millions of times.

This profound mechanism ensures that the image output created is entirely new, original, and unique— regardless of the dataset used to train the AI. The AI does not copy; it learns, associates, and creates in ways that humans could never conceive. In fact, each generation of the diffusion process makes it impossible for the AI to create the same image twice, as Gaussian noise is truly stochastic. The resulting artwork is not just a product of random numbers and machine computations—it’s a testament to the power of artificial intelligence as a tool for human creativity.

By appreciating the intricacies of this process, we can better understand the significance of the debate surrounding copyright and AI-generated art. After all, when an artist uses such an advanced tool to create a piece of art, who should the rights belong to—the tool, or the artist who wielded it?

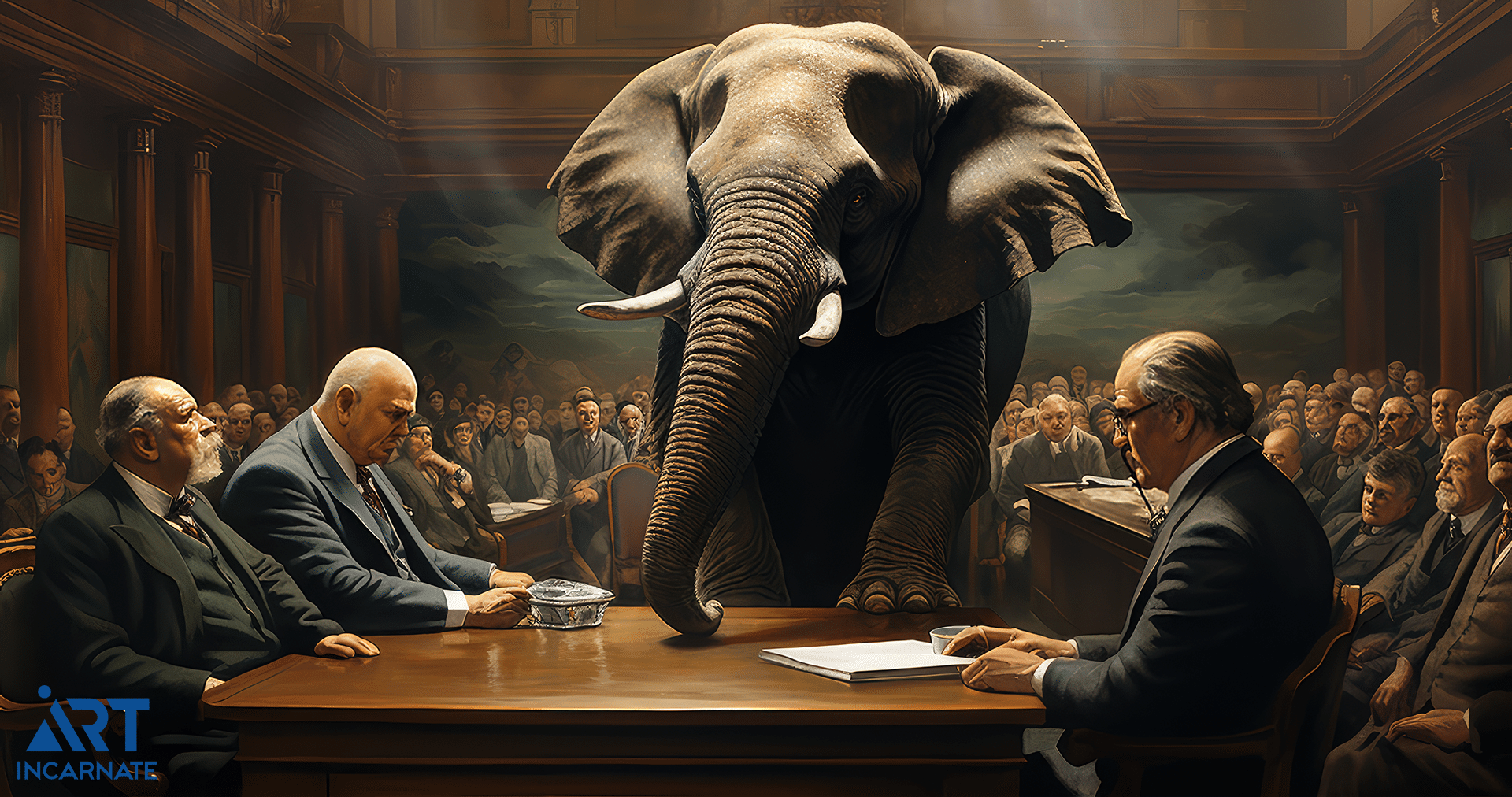

To lighten the mood, let’s engage in a fun mental exercise. Picture an elephant. Odds are, a majestic pachyderm has materialized in your mind’s eye, complete with its large, floppy ears and a long, snaking trunk. Now, add a baby elephant beside it. Picture them gallivanting through the sweeping grasslands of the Serengeti. Visualize the elder elephant playfully spraying water from its trunk, the droplets catching the light and sparkling like diamonds.

Have these images formed in your mind? Could you see the elephants in all their glory? Of course, you could! But why? It’s because you’ve seen elephants before, whether in real life, in a nature documentary, or in an art piece. Yet, in visualizing these scenes, did you “copy” the elephants you’ve seen before?

Hardly so. We wouldn’t use “copying” to describe this mental process. Instead, you’ve drawn upon your accumulated knowledge and experiences to imagine the essence of an elephant. This ability to form mental images, to create a vivid scene from words and memories, is a testament to human creativity and imagination.

Now, consider the prospect of technology enabling us to project these mental images onto a screen. While we may not be there quite yet, AI is already pioneering the way, offering text-to-image, video, and audio capabilities, and introducing new innovations daily. The objective here isn’t to create a system that merely reproduces existing images – we’ve had photocopiers for that. Instead, we’re striving to emulate human learning and creativity.

The principles underpinning AI’s learning mechanisms are akin to our neural pathways. They recall how we recognize and recreate familiar things after repeated exposure. Traditionally, artists had the unique skill of translating their internal visions onto canvas or sculpture. Now, AI provides a tool for everyone to manifest their imaginations, to bring their mind’s eye into the tangible world.

This concept underlies Art Incarnate, Jason M. Allen’s luxury AI company, which carries the fitting slogan, “Your Vision Creates Reality.” As we consider the impact of AI on art and copyright law, let’s remember that we are not creating mindless copy machines. Instead, we are crafting intelligent entities that learn, interpret, and create, much like us. And in doing so, we bring the reality of our visions into the palm of our hands.

When game designer Jason M. Allen first started exploring the boundless potential of artificial intelligence in his artwork, he knew he was stepping into uncharted territory. With each keystroke, each variation, and each parameter adjustment in the AI tool he was using, he was breathing life into something unprecedented. What he didn’t know, however, was that his journey would steer him headlong into a legal quagmire that would expose the dated and restrictive practices of the United States Copyright Office (USCO).

Allen’s seminal work, Théâtre d’Opéra Spatial, a blend of human ingenuity and algorithmic precision, was rejected by the USCO on the grounds that it was created with AI assistance. The USCO maintained that because AI was involved in the process, the work couldn’t be protected under copyright law. But the question looming at the heart of this standoff is this: should an artist’s creative vision be denied legal protection simply because they used AI as a tool in their process?

On December 13, 2022, Jason Allen, the avant-garde AI artist, found his application for copyright registration unceremoniously denied, marked only with a succinct one-page document from the United States Copyright Office (USCO). Undeterred, Allen, along with his attorney Tamara Pester, sought to challenge the verdict, promptly filing their First Request for Reconsideration on January 24, 2023.

Passionate about the fight for expressive rights in the sphere of AI artistry, Allen initiated the COVER protest (Copyright Obstruction Violates Expressive Rights) in the wake of his filing. This movement marked a stark protest against the denial of copyright to AI-generated art, thrusting the issue into the limelight of legal and artistic discourse.

The plot thickened on March 16, 2023, as the USCO released its document titled “Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence.” This exhaustive piece, widely perceived as a mental gymnastics exercise, sought to elucidate the criteria for copyright registration, further complicating the conversation surrounding AI-generated works.

Intriguingly, the Office took a little longer than the stipulated four months to review Allen’s Request for Reconsideration, ultimately delivering a 12-page document on June 6, 2023, denying Allen’s claim once again. Undeterred by the protracted process and unyielding denial, Allen and Pester wasted no time in filing their Second Request for Reconsideration on July 12, 2023. Their resolve, coupled with their tireless advocacy for AI creativity, continues to disrupt and redefine the boundaries of copyright law and artistic expression in the era of artificial intelligence.

In challenging the USCO’s decision, Allen has exposed the murky waters of copyright law and how it is failing to keep up with the rapid evolution of artistic mediums. In an age where AI tools are increasingly common, the struggle between Allen and the USCO prompts us to ask: Where should we draw the line between the tool and the author in copyright considerations?

As it stands, the USCO’s stance implies that AI isn’t just a tool but a co-creator or even the author. This perspective fails to distinguish between the AI’s role as an extension of the artist’s creative vision and the AI as an independent entity capable of original creation – a distinction that is crucial not only for artists working with AI today but also for the future of digital creativity.

In the throes of his legal battle, Allen has spotlighted the inconsistencies in the USCO’s application of copyright laws. The Office has touted the need for “human authorship” while seemingly failing to comprehend that, in the case of AI-assisted art, the AI is not an independent author but a medium through which the artist expresses their creativity.

In a fascinating twist, the stance of the Copyright Office inadvertently concedes that AI-generated images, in their nature, don’t infringe upon copyright laws. The crux of this observation lies in the Office’s lack of any assertion or inference suggesting that the use of AI could result in copyright infringement. In their dismissals of AI registrations, they have never pointed to infringement as a reason for the rejection.

Furthermore, the acceptance of AI-generated images as a part of the creative process by the Office adds another layer of complexity to their stance. If they acknowledge AI’s role in the creation of artistic works, they implicitly acknowledge that the use of AI tools doesn’t infringe on existing copyrights. Not to mention a method for human creativity.

In essence, their stance appears to acknowledge that AI, as a tool or medium, doesn’t violate copyright laws or engage in copyright infringement. However, it begs the question: If AI-generated images don’t infringe upon copyright laws and are considered an acceptable part of the creative process, why then should they be denied copyright protection when used in the creation of a final artwork? This thought-provoking question is a striking inconsistency in the Office’s approach and further underscores the need for a comprehensive review and revision of current copyright laws as they pertain to AI-assisted creativity.

In Jason Allen’s view, aside from their strong arguments and counterpoints within their Requests for Reconsiderations, the principle of Occam’s Razor gains significant clarity; the simplest and most factual explanation for the creation of an AI-generated image is simply “the human user input a prompt and created the output image using an AI generative tool.” The USCO’s rationalizations, though, are akin to a tumble down the rabbit hole of the preposterous, where one must cavort with the inane and entertain the most extravagantly contorted notions, much like in a Lewis Carroll fantasia.

While Allen’s case might seem like an isolated incident, it is emblematic of a larger issue plaguing the digital art world. The USCO’s outdated interpretation of copyright law is a noose around the neck of innovation, deterring artists from exploring AI as a creative medium for fear of being denied copyright protection for their work.

The broader implications of this legal standoff are chilling. The potential for AI to revolutionize the arts is immense, but without clear guidelines on copyright protection, we risk stifling that creative potential before it even has a chance to flourish.

Moreover, the USCO’s restrictive stance could potentially undervalue AI-assisted art in the commercial market, leaving artists vulnerable to exploitation. After all, if an AI-assisted artwork is deemed ineligible for copyright protection, what’s to stop others from freely reproducing and profiting off an artist’s original work without their consent?

*Enter angry, vulnerable, narcissistic artist*

The argument that AI-generated images infringe upon artists’ copyrights is not without its detractors, especially within the AI community. Stability AI, a leading company in deep learning and text-to-image model AI, stands as a sturdy counterexample to such claims.

In the recent lawsuit brought against them, a group of artists asserted that Stability AI’s product, Stable Diffusion (trained on billions of copyrighted images from the LAION-5B dataset without compensation and allegedly without consent), is tantamount to theft. Furthermore, they purport that if AI products like Stable Diffusion continue to operate in their current fashion, artists’ livelihoods would be in jeopardy, eventually eliminating “artist” as a viable career path.

However, Stability AI retorts that the artists “fail to identify a single allegedly infringing output image, let alone one that is substantially similar to any of their copyrighted works.” The crux of their argument lies in the unique nature of AI operation and output, which we’ve previously dissected in depth.

When an AI like Stable Diffusion learns from an image, it is not copying or reproducing the image, but rather learning from it. It learns to recognize lines, shapes, colors, and spacing, combining this visual data with corresponding textual descriptions. It then employs the deep learning method of diffusion models to generate entirely new and original images.

As such, the images produced are not reproductions of the training data but entirely new works of art, extracted from randomly sampled noise and reverse-engineered using methods the AI has practiced countless times. Each output is wholly unique, impossible to reproduce even by the same AI, and hence bears no substantial similarity to the images in the training data.

So, when the lawsuit states, “Stability AI, Midjourney, and DeviantArt are appropriating the work of thousands of artists with no consent, no credit, and no compensation,” it is crucial to remember that the process of AI learning is not an act of appropriation but of interpretation and creation. Drawing parallels with the music industry, if an artist samples a note from a copyrighted song to create a new composition, it doesn’t make the new composition a copy of the original work. The AI, much like the artist, is sampling, learning, and creating something new, not copying.

The future of art will undoubtedly involve AI technology. To assert that AI will eliminate “artist” as a viable career path is to overlook the tremendous potential AI holds in enhancing artistic creativity. The debate then is not about whether AI infringes upon copyright laws but about how we redefine these laws to accommodate the emergence of AI as a tool for human creativity.

The time has come for a comprehensive reevaluation of copyright law. As technology continues to advance at an unprecedented rate, it is imperative that legal frameworks adapt in tandem to adequately protect artists and their creative expressions.

Allen’s battle with the USCO isn’t just about one piece of art. It is about advocating for thousands of artists who are pushing the boundaries of creativity with AI. It is about challenging antiquated notions of authorship and ushering in a new era of copyright law that not only respects but also encourages innovation.

The world is watching as this modern-day David takes on the Goliath of copyright law. It’s high time we, as a society, rally behind the artists and innovators who are reshaping our understanding of what constitutes art in the digital age. We must recognize that the tools of creation do not diminish the value of the creative act. Instead, they expand the canvas upon which artists can express their imagination.

Today, the canvas of creativity extends far beyond the physical medium, encompassing the digital realm and all the tools it harbors, including AI. The question is, will our legal frameworks evolve to recognize and protect this new age of artistic expression, or will they remain rooted in the past, denying artists the credit they deserve? As Allen’s case unfolds, the answer hangs in the balance.

0 Comments